Lumbar disc herniation, often colloquially referred to as a ‘slipped disc’, is a prevalent medical condition characterized by the displacement of disc material beyond the intervertebral disc space. Manifesting through symptoms such as lower back pain, sciatica (shooting nerve pain down the leg), and potential neurological impairments like numbness or weakness in the lower extremities, the condition is common, especially in the middle-aged and elderly populations.

Overview of common treatment methods, emphasizing surgical and non-surgical approaches

- Treating lumbar disc herniation involves a spectrum of approaches, ranging from conservative, non-surgical methods to more invasive surgical interventions.

- These interventions can be effective, with a review of the literature indicating that approximately 90% of patients experience significant relief from these non-surgical interventions (4).

- The initial line of treatment usually includes non-surgical methods such as pain medication, physical therapy, epidural injections, and lifestyle modifications.

- However, in cases where these treatments fail to alleviate symptoms or if neurological deficits are present, surgical options become necessary.

- These may encompass procedures like microdiscectomy, laminectomy, or in some cases, spinal fusion or artificial disc replacement.

- Multiple studies, such as those conducted by Atlas, et al., (2005) and Weinstein, et al., (2008), have demonstrated that patients who undergo surgery often experience faster relief of symptoms and improved function compared to those who continue with conservative treatment (1)(8).

Causes and Risk Factors for Lumbar Disc Herniation

Age-Related Degeneration:

Our intervertebral discs, the soft, gel-like cushions between our vertebrae, naturally lose water content as we age, become less flexible, and are more likely to rupture or tear with a slight twist or pressure. This is a common cause of disc herniation and is backed by research (7).

Physical Strain and Trauma:

- Excessive strain on the back from heavy lifting or twisting movements can cause lumbar disc herniation. These actions can place too much pressure on the disc, causing it to rupture or herniate.

- Traumatic injury, such as a fall or a car accident, can cause sudden and severe pressure on the disc, leading to herniation (6).

Genetic Predisposition:

Certain individuals may be genetically predisposed to developing disc herniations. If family members have had disc herniations, particularly at a young age, you may be at higher risk. Studies have found specific genes that are associated with an increased risk of developing the condition (2).

Lifestyle Factors:

Smoking:

Nicotine decreases the ability of disc cells to absorb the nutrients they need from the bloodstream, hastening disc degeneration. A study conducted by Shiri, et al., (2010) identified smoking as a significant risk factor for lumbar disc herniation (5).

Lack of Exercise: Regular exercise helps maintain healthy discs by improving spinal mobility and circulation, which helps nourish the discs. A sedentary lifestyle, on the other hand, can contribute to disc degeneration and subsequent herniation (3).

Occupational Hazards: Jobs that involve heavy or repetitive lifting, bending, twisting, or whole-body vibration (like driving) can place significant stress on your lower spine, increasing the risk of a disc herniating (5).

It’s important to note that while these are common causes and risk factors, lumbar disc herniation can sometimes occur without a clear cause or specific risk factor. In some cases, a disc can herniate from simple, everyday activities like bending over to tie a shoelace or lifting a light object.

Read More: 6 Tips for Relieving Pain From Herniated Discs or Disc Prolapse

Symptoms of Lumbar Disc Herniation

Lower Back Pain: This is often the first symptom experienced by patients with a lumbar disc herniation. The pain can range from mild discomfort to severe, debilitating pain. The intensity and duration of the pain can vary depending on factors such as the location of the herniation and the degree of nerve compression. The pain may worsen with certain movements or positions such as bending forward, coughing, or sneezing (11).

Sciatica:

Sciatica is a term for discomfort that travels down the sciatic nerve’s course, which arises from your lower back and branches out into your hips, buttocks, and down each leg. Most often, sciatica just affects one side of your body. The sciatic nerve, which runs from the buttock to the back of the leg, can become compressed by a herniated disc, resulting in an intense, shooting pain. A study by Konstantinou, et al., (2015) found that sciatica was present in a significant number of patients with lumbar disc herniation (9).

Numbness or Tingling: This sensation, often described as ‘pins and needles’, can occur in the lower extremities (i.e., the legs and feet). Numbness and tingling in the legs or feet can result from nerve compression due to a herniated disc (12). This happens because the herniated disc may be pressing against nerves that control sensory signals in these areas.

Muscle Weakness: In severe cases, herniation can cause muscle weakness if the nerves that control the leg muscles are affected. This might make tasks that were once easy, like lifting objects or walking, more challenging.

Diagnostic Methods for Lumbar Disc Herniation

Diagnosing lumbar disc herniation typically involves a combination of clinical evaluation and imaging techniques. Here’s a step-by-step overview of the process:

1. Clinical History and Physical Examination:

The diagnostic process starts with a detailed discussion about the patient’s symptoms and medical history. The doctor will ask about the nature of the pain, its location, any activities or positions that worsen or relieve the pain, and any associated symptoms such as numbness, tingling, or weakness in the legs.

The doctor will evaluate the patient’s posture, range of motion, and physical condition during the physical examination. Specific tests may be performed to check for pain, numbness, or weakness in different parts of the leg, known as a neurological examination. One common test is the straight leg raise test, where the patient lies on their back and the doctor slowly lifts the patient’s leg. If this causes or exacerbates the patient’s sciatic pain, it can be an indication of a herniated disc.

2. Imaging Techniques:

If a herniated disc is suspected based on the patient’s history and physical examination, the doctor will likely order imaging studies to confirm the diagnosis and identify the exact location and size of the herniation. The most common imaging techniques include:

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging):

MRI is the most sensitive and accurate imaging test for diagnosing disc herniation and can provide detailed images of the spinal cord, nerve roots, and surrounding areas (13). It can reveal the location and size of the herniation, as well as any associated nerve compression.

CT (Computed Tomography) scan:

While not as sensitive as MRI, CT scans can still be useful in diagnosing lumbar disc herniation, especially if the patient cannot undergo an MRI (19). Although it’s typically not as good as MRI at imaging the soft tissues. Sometimes, a CT scan may be combined with a myelogram, where a contrast dye is injected into the spinal fluid to highlight the nerves and reveal any compression.

X-ray:

X-rays are less effective in diagnosing disc herniation as they do not show the soft tissues of the disc and nerve roots. However, they can rule out other conditions such as fractures or tumors (19).

3. Electromyography (EMG):

EMG can be used to evaluate nerve function and can help confirm a diagnosis of lumbar disc herniation, especially when other tests are inconclusive. This test measures the electrical activity of the muscles and can help determine if there’s any nerve compression due to a herniated disc.

These diagnostic methods combined provide a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s condition, guiding the doctor in creating an effective treatment plan.

Read More: The best treatment of PLID/ Disc herniation / Disc prolapse in Bangladesh

Surgical Treatments for Lumbar Disc Herniation

Various surgical techniques & effectiveness of each surgical treatment.

A. Several surgical techniques can be used to treat lumbar disc herniation, depending on the severity and nature of the condition.

Discectomy/Microdiscectomy:

A discectomy is a surgical procedure to remove the herniated portion of a disc to relieve the pressure on nearby nerves. When this procedure is performed with the aid of a special microscope to view the disc and nerves, it’s known as a microdiscectomy. The microscope allows the surgeon to make a smaller incision, reducing damage to the surrounding tissues.

This is a common surgical treatment for lumbar disc herniation and is generally effective at relieving symptoms. According to a study by Weber, H., (1994), 84% of patients experienced good or excellent results after microdiscectomy (24). However, back pain may persist in some cases. The advantage of microdiscectomy is that it is less invasive, which can lead to shorter recovery times and less post-operative pain compared to traditional open surgery.

Laminectomy/Laminotomy:

In a laminectomy, the surgeon removes the entire bony lamina (a portion of the vertebral bone) to decrease spinal pressure. A laminotomy, on the other hand, involves the removal of a small portion of the lamina to relieve pressure on the nerve roots. These procedures are often performed when the patient has more severe or persistent symptoms.

These procedures can be very effective for relieving symptoms associated with lumbar disc herniation, especially in cases where spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal) is also present. The majority of patients report a significant decrease in pain and improvement in function after the surgery. Research shows that laminectomy effectively relieves symptoms in approximately 64%-83% of patients (19). However, it is a more invasive procedure, with a higher risk of complications and a longer recovery time compared to less invasive surgeries.

Artificial Disc Surgery:

If the entire disc must be removed, an artificial disc can be inserted in its place. The goal of this procedure is to allow continued motion at that spinal level and to reduce the chance of degeneration in the discs above and below the affected disc.

Studies have shown that artificial disc surgery can be as effective as spinal fusion for relieving pain and improving function. One potential advantage of this procedure is that it maintains more normal spinal movement compared to fusion. However, not all patients are good candidates for this procedure, and long-term data on the durability of artificial discs is still being collected. It is less commonly used than discectomy or laminectomy (20).

Spinal Fusion:

Spinal fusion is a procedure where the problematic disc is removed and the adjacent vertebrae are fused together, often with a bone graft. Over time, the graft will merge with the existing bones and form a single, solid bone. This procedure is performed to improve stability and prevent movement that could cause pain.

Spinal fusion can be highly effective for eliminating motion at the painful disc level and providing pain relief. However, it has a higher complication rate and longer recovery period than other surgeries (22). There is also the potential for a phenomenon known as adjacent segment disease, where the discs above or below the fusion experience increased stress and potentially accelerate degenerative changes.

Endoscopic Discectomy:

This is a minimally invasive procedure where the surgeon uses an endoscope to visualize the disc and nerves. A small incision is made, through which the endoscope and surgical tools are inserted. The herniated portion of the disc is then removed. It can lead to less muscle damage, less postoperative pain, and faster recovery than traditional surgery (23).

This minimally invasive procedure has been shown to effectively relieve sciatica symptoms in patients with lumbar disc herniation. Most patients can return to normal activities more quickly compared to traditional open surgery. However, as with any surgical procedure, there are risks, including nerve damage and infection.

Percutaneous Disc Decompression:

In this minimally invasive procedure, a special tool is inserted through a small incision in the skin and muscle to reach the herniated disc. The tool is then used to remove a portion of the disc, reducing its size and the pressure on the nerve. This is typically used for contained disc herniations and has less postoperative pain and shorter recovery time, but may not be as effective for larger, non-contained herniations (14).

This procedure has been found to significantly reduce pain and improve function in many patients. However, as it’s a relatively newer technique, more research is needed to understand its long-term effectiveness and potential complications.

Potential risks and complications associated with surgical treatments

while surgical treatments can provide significant relief from the symptoms of lumbar disc herniation, they are not without risks and potential complications. Here’s an overview:

Infection: This is a risk with any surgery and can lead to serious complications if not treated promptly (16). This can occur at the incision site or deep within the body. If detected early, infections are typically treatable with antibiotics. In rare cases, a deep infection may require additional surgery.

Bleeding: There is always a risk of bleeding during and after surgery. Blood loss during surgery can lead to complications, but is usually well-controlled during spinal surgeries (15). However, in rare situations, a significant blood loss can occur that may require a blood transfusion.

Nerve damage: The spine is a complex structure that houses the spinal cord and nerve roots. Despite the surgeon’s best efforts to avoid it, there’s a risk of nerve damage during surgery which can lead to weakness, loss of sensation, or even paralysis (18).

Dural tear: The dura is a membrane that covers the spinal cord and contains cerebrospinal fluid. If the dura is inadvertently torn during surgery, it can lead to a cerebrospinal fluid leak. Most of these tears can be repaired during the surgery. But occasionally a persistent leak can lead to headaches or, in rare cases, a brain infection called meningitis.

Recurrence of disc herniation: Even after successful surgery, there’s a risk that disc herniation can recur at the same location. The risk is believed to be higher in individuals who engage in heavy physical activities soon after surgery. According to a study by Lebow, et al., (2012), this occurs in about 5%-10% of cases (34).

Adjacent segment disease: After a spinal fusion, the segments above and below the fused vertebrae must take on more stress, which can accelerate degeneration in these discs and potentially lead to additional herniations. It is a long-term complication of spinal fusion (21).

Failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS): This refers to a condition where the patient experiences continued pain after surgery. FBSS can be due to several factors, including recurrent disc herniation, persistent post-operative nerve compression, or nerve damage during surgery. It is associated with multiple spine surgeries and can be difficult to treat.

It’s important for patients to understand these risks before deciding on surgery. The surgeon will often discuss these potential complications and their likelihood based on the patient’s individual circumstances. It’s also important to consider that these risks must be weighed against the potential benefits of surgery, including pain relief, improved function, and an enhanced quality of life.

Read More: Self-diagnosis of lumbar intervertebral disc prolapse/PLID/Disc Herniation

Strategies to mitigate these risks

There are several strategies to mitigate the risks associated with surgery for lumbar disc herniation. These strategies can be broadly categorized into preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative measures.

Preoperative Measures:

Health Optimization: Prior to surgery, optimizing the patient’s health can significantly reduce the risk of complications. This could involve managing existing medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypertension), encouraging cessation of smoking, and improving nutritional status (25).

Preoperative Testing: Routine preoperative tests can help identify potential problems that could lead to surgical complications. These might include blood tests, radiological imaging, and cardiac tests depending on the patient’s health history (30).

Medication Management: Some medications, particularly those that affect blood clotting (like aspirin or anticoagulants), may need to be managed in the days leading up to the surgery to reduce the risk of bleeding. However, this should always be done under the supervision of a healthcare provider (28).

Intraoperative Measures:

Sterile Techniques: Maintaining sterile techniques throughout the surgery is crucial in preventing surgical site infections (SSI). This includes hand and arm preparation, proper surgical attire, and strict aseptic techniques during the procedure (25).

Experienced Surgeon and Team: The experience and skill level of the surgeon and surgical team have been shown to directly influence surgical outcomes and complications.

Appropriate Surgical Technique: Using appropriate and up-to-date surgical techniques can help to minimize the risk of complications. This may also include the use of intraoperative imaging to enhance precision.

Postoperative Measures:

Postoperative Monitoring: Regular postoperative monitoring of the patient can help to detect and address complications early. This includes monitoring of vital signs, pain levels, and neurological status (26).

Infection Prevention: Postoperative infection prevention measures may include the use of prophylactic antibiotics, regular dressing changes, and educating the patient on the signs of infection (25).

Pain Management: Adequate postoperative pain management can enhance recovery, decrease the length of hospital stay, and minimize the risk of chronic pain (27).

Rehabilitation: Postoperative rehabilitation programs, including physical therapy and exercises, can help to improve mobility, strength, and overall recovery (29).

While these measures can significantly reduce the risks associated with surgery, they cannot eliminate them completely. It’s important for patients to fully understand the potential risks and discuss any concerns with their healthcare provider before deciding on surgery.

When is Surgery Necessary?

Surgical intervention for lumbar disc herniation is generally considered when less invasive treatments have failed to provide sufficient relief or when the patient’s symptoms are severe or worsening. Here are some common indicators for considering surgical intervention:

Ineffectiveness of Conservative Treatment: If conservative treatments, such as physical therapy, pain management with medications, and epidural steroid injections, have not alleviated the patient’s symptoms after a reasonable period (usually 6-12 weeks), surgical intervention might be considered (37).

Severity of Symptoms: Severe pain that impairs the quality of life, disrupts sleep, or hinders everyday activities might necessitate surgical intervention (32).

Neurological Symptoms: If the patient has signs of nerve damage, such as weakness, numbness, tingling in the legs, or loss of bladder or bowel control, surgery may be indicated to relieve pressure on the nerves and prevent permanent damage (37).

Progressive Neurological Deficit: If the patient’s neurological symptoms are getting worse over time, this is often a sign that the disc herniation is causing ongoing nerve compression or damage. This is an important indicator for surgical intervention (32).

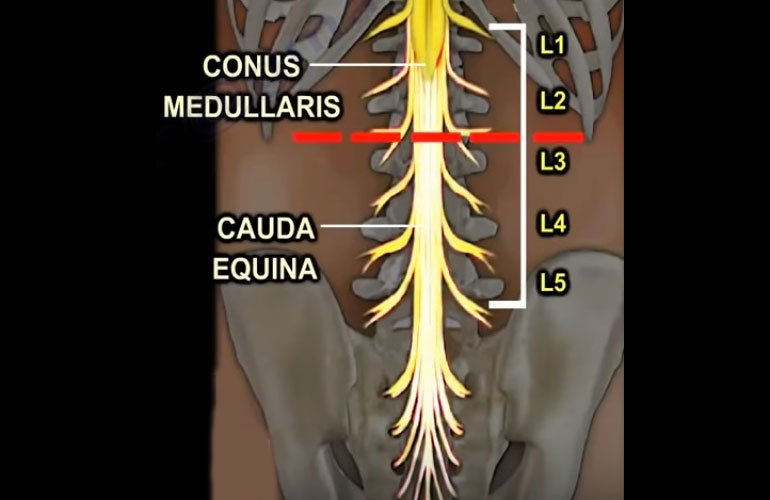

Cauda Equina Syndrome:

This is a rare but serious condition where the nerves at the end of the spinal cord are compressed, causing loss of bowel and bladder control, sexual dysfunction, and weakness or numbness in both legs. It’s considered a surgical emergency as it can lead to permanent paralysis if not treated promptly (36).

Duration of Symptoms: Persistent symptoms lasting for more than six weeks despite conservative treatments can also be an indication for surgery (32).

These indicators are guidelines and the decision to proceed with surgery is typically made on a case-by-case basis, considering the overall health of the patient, the specific details of the herniation, the severity of the symptoms, and the patient’s personal preferences. The goal is to choose the treatment option that will best alleviate the patient’s symptoms and improve their quality of life with the least risk.

Read More: What Not to Do When Living with a Herniated Disc

Comparative Analysis: Surgery vs. Non-Surgical Treatments

A comparative analysis of surgery versus non-surgical treatments for lumbar disc herniation involves looking at the efficacy, risks, recovery period, and long-term outcomes of each approach.

Surgery

Efficacy: Surgery can be highly effective for treating lumbar disc herniation, particularly for patients whose symptoms have not improved with conservative treatments. Research shows that Surgery generally provides faster relief of symptoms and is more effective for people with persistent, severe symptoms (37).

Risks: As discussed earlier, potential risks include infection, nerve damage, dural tear, and recurrence of disc herniation, among others (34).

Recovery Period: The recovery period can vary depending on the type of surgery, but typically, patients may require several weeks to a few months for recovery (35).

Long-term Outcomes: In the long term, successful surgery can provide significant pain relief and improve the patient’s ability to function and quality of life. However, some patients may still experience residual pain or functional limitations, and there is a risk of reoperation in the future (33). There are potential long-term risks to consider, like the development of adjacent segment disease after spinal fusion.

Non-Surgical Treatments

Efficacy: Non-surgical treatments, including physical therapy, medications, and epidural injections can be effective for many people, especially those with mild symptoms and no significant neurological deficits (37).

Risks: Risks are generally lower than with surgery and may include potential side effects of medications (e.g., gastrointestinal issues, allergic reactions) and potential risks associated with spinal injections (e.g., infection, nerve damage) (31).

Recovery Period: As non-surgical treatments are less invasive; they usually do not require a significant recovery period. However, it can take some time for these treatments to have an effect, and multiple treatment sessions may be necessary (35).

Long-term Outcomes: Long-term outcomes can be variable. Some people experience long-term relief, while others may see their symptoms gradually return over time (37). It’s also worth noting that non-surgical treatments generally manage the symptoms rather than resolving the underlying issue of the herniated disc.

The decision between surgical and non-surgical treatments should be based on the individual patient’s symptoms, overall health, personal preferences, and the potential benefits and risks of each option. It’s crucial to have a detailed discussion with a healthcare provider before making this decision.

Future Directions and Conclusion

As medical technology and understanding of spinal pathology continue to evolve, the future holds promise for further improvements in surgical techniques for lumbar disc herniation. One area of research is the development of new, less invasive surgical procedures that can reduce complications and speed recovery. The integration of advanced imaging technologies and robotics in spinal surgery may allow for even more precise operations. The use of biological therapies, such as stem cell therapy or growth factors, which aim to promote the body’s natural healing processes, also represents an exciting avenue for future research. Furthermore, understanding the genetic factors that contribute to disc herniation could lead to preventative strategies or targeted treatments.

Surgery plays a crucial role in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation, particularly for patients who have not found relief from conservative treatments, or who have severe or worsening symptoms. While surgical intervention carries potential risks, it can also provide significant and often rapid relief from pain and other symptoms, improving the quality of life for many patients.

FAQ’s

Q: What is a lumbar disc herniation?

A: Lumbar disc herniation is a condition where one of the discs in the lower part of your spine, known as lumbar discs, ruptures or herniates. This leads to the inner material of the disc protruding into the spinal canal, which can cause pressure on the nerves and result in pain, numbness, or weakness in the lower back and legs.

Q: What are the typical non-surgical treatments for lumbar disc herniation?

A: Non-surgical treatments for lumbar disc herniation can include pain medication, physical therapy, exercises, corticosteroid injections, and sometimes, lifestyle modifications. The goal of these treatments is to reduce pain and inflammation, enhance mobility, and improve quality of life.

Q: When is surgery considered for treating lumbar disc herniation?

A: Surgery is usually considered when non-surgical treatments have not provided adequate relief, or if the patient is experiencing severe or worsening symptoms such as significant pain, numbness, muscle weakness, or loss of bladder or bowel control.

Q: What types of surgery are performed for lumbar disc herniation?

A: There are several types of surgery for lumbar disc herniation, including a discectomy (removal of the herniated part of the disc), a laminectomy (removal of part of the bone overlying the spinal canal), or spinal fusion (connecting two or more bones in your spine together). The type of surgery will depend on the patient’s specific condition and the surgeon’s assessment.

Q: What are the potential risks of surgery for lumbar disc herniation?

A: Like any surgery, there are potential risks and complications. These can include infection, nerve damage, spinal fluid leaks, blood clots, persistent pain, and in some cases, the need for additional surgeries. It’s crucial to discuss these potential risks and benefits with your surgeon to make an informed decision.

Q: What is the recovery process like after surgery for lumbar disc herniation?

A: Recovery can vary greatly depending on the specific procedure and individual patient factors. Generally, patients will spend a few days in the hospital following surgery. Physical therapy usually begins as soon as possible to help regain strength and mobility. Full recovery may take several weeks to months.

Q: How successful is surgery in treating lumbar disc herniation?

A: Surgery for lumbar disc herniation can be quite successful in relieving symptoms. A majority of patients report significant improvement in their pain and mobility. However, as with any medical procedure, the success of the surgery depends on a variety of factors, including the severity of the herniation, the patient’s overall health, and the precision of the surgical procedure.

References

1.Atlas, S.J., Keller, R.B., Wu, Y.A., Deyo, R.A. and Singer, D.E., 2005. Long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of sciatica secondary to a lumbar disc herniation: 10 year results from the maine lumbar spine study. Spine, 30(8), pp.927-935.

https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/Fulltext/2005/04150/Recurrent_Lumbar_Disc_Herniation__Results_of.16.aspx

2.Battié, M.C., Videman, T., Levälahti, E., Gill, K. and Kaprio, J., 2008. Genetic and environmental effects on disc degeneration by phenotype and spinal level: a multivariate twin study. Spine, 33(25), pp.2801-2808.

https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/fulltext/2008/12010/genetic_and_environmental_effects_on_disc.16.aspx

3.Heneweer, H., Staes, F., Aufdemkampe, G., van Rijn, M. and Vanhees, L., 2011. Physical activity and low back pain: a systematic review of recent literature. European Spine Journal, 20, pp.826-845.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00586-010-1680-7

4.Jacobs, W., Van der Gaag, N.A., Tuschel, A., de Kleuver, M., Peul, W., Verbout, A.J. and Oner, F.C., 2012. Total disc replacement for chronic back pain in the presence of disc degeneration. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (9).

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008326.pub2/abstract

5.Shiri, R., Karppinen, J., Leino-Arjas, P., Solovieva, S. and Viikari-Juntura, E., 2010. The association between smoking and low back pain: a meta-analysis. The American journal of medicine, 123(1), pp.87-e7.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S000293430900713X

6.Takatalo, J., Karppinen, J., Niinimäki, J., Taimela, S., Näyhä, S., Järvelin, M.R., Kyllönen, E. and Tervonen, O., 2009. Prevalence of degenerative imaging findings in lumbar magnetic resonance imaging among young adults. Spine, 34(16), pp.1716-1721.

https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/fulltext/2009/07150/Prevalence_of_Degenerative_Imaging_Findings_in.14.aspx

7.Urban, J.P. and Roberts, S., 2003. Degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Res Ther, 5(3), pp.1-11.

https://arthritis-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/ar629

8.Weinstein, J.N., Lurie, J.D., Tosteson, T.D., Tosteson, A.N., Blood, E., Abdu, W.A., Herkowitz, H., Hilibrand, A., Albert, T. and Fischgrund, J., 2008. Surgical versus non-operative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: four-year results for the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). Spine, 33(25), p.2789.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2756172/

9.Konstantinou, K., Dunn, K.M., Ogollah, R., Vogel, S. and Hay, E.M., 2015. Characteristics of patients with low back and leg pain seeking treatment in primary care: baseline results from the ATLAS cohort study. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 16(1), pp.1-11.

https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-015-0787-8

10.Lurie, J. and Tomkins-Lane, C., 2016. Management of lumbar spinal stenosis. Bmj, 352.

https://www.bmj.com/content/352/bmj.H6234.abstract

11.Maher, C., Underwood, M. and Buchbinder, R., 2017. Non-specific low back pain. The Lancet, 389(10070), pp.736-747.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673616309709

12.Radcliff, K., Kepler, C., Hilibrand, A., Rihn, J., Zhao, W., Lurie, J., Tosteson, T., Vaccaro, A., Albert, T. and Weinstein, J., 2013. Epidural steroid injections are associated with less improvement in the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis: a subgroup analysis of the SPORT. Spine, 38(4), p.279.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3622047/

13.Wassenaar, M., van Rijn, R.M., van Tulder, M.W., Verhagen, A.P., van der Windt, D.A., Koes, B.W., de Boer, M.R., Ginai, A.Z. and Ostelo, R.W., 2012. Magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosing lumbar spinal pathology in adult patients with low back pain or sciatica: a diagnostic systematic review. European spine journal, 21, pp.220-227.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00586-011-2019-8

14.Bhagia, S.M., Slipman, C.W., Nirschl, M., Isaac, Z., El-Abd, O., Sharps, L.S. and Garvin, C., 2006. Side effects and complications after percutaneous disc decompression using coblation technology. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 85(1), pp.6-13.

https://journals.lww.com/ajpmr/Fulltext/2006/01000/Side_Effects_and_Complications_After_Percutaneous.2.aspx

15.Cheriyan, T., Maier II, S.P., Bianco, K., Slobodyanyuk, K., Rattenni, R.N., Lafage, V., Schwab, F.J., Lonner, B.S. and Errico, T.J., 2015. Efficacy of tranexamic acid on surgical bleeding in spine surgery: a meta-analysis. The Spine Journal, 15(4), pp.752-761.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1529943015000297

16.Ghobrial, + Gonzalez, A.A., Jeyanandarajan, D., Hansen, C., Zada, G. and Hsieh, P.C., 2009. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring during spine surgery: a review. Neurosurgical focus, 27(4), p.E6.

https://thejns.org/focus/view/journals/neurosurg-focus/27/4/article-pE6.xml

17.Lebow, R.L., Adogwa, O., Parker, S.L., Sharma, A., Cheng, J. and McGirt, M.J., 2011. Asymptomatic same-site recurrent disc herniation after lumbar discectomy: results of a prospective longitudinal study with 2-year serial imaging. Spine, 36(25), pp.2147-2151.

https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/fulltext/2011/12010/Asymptomatic_Same_Site_Recurrent_Disc_Herniation.7.aspx

18.Leven, D., Passias, P.G., Errico, T.J., Lafage, V., Bianco, K., Lee, A., Lurie, J.D., Tosteson, T.D., Zhao, W., Spratt, K.F. and Morgan, T.S., 2015. Risk factors for reoperation in patients treated surgically for intervertebral disc herniation: a subanalysis of eight-year SPORT data. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume, 97(16), p.1316.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5480260/

19.Lurie, J.D., Tosteson, T.D., Tosteson, A.N., Zhao, W., Morgan, T.S., Abdu, W.A., Herkowitz, H. and Weinstein, J.N., 2014. Surgical versus non-operative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: eight-year results for the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). Spine, 39(1), p.3.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3921966/

20.Lu, + Ding F, Jia Z, Zhao Z, Xie L, Gao X, Ma D, Liu M. Total disc replacement versus fusion for lumbar degenerative disc disease: a systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Eur Spine J. 2017 Mar;26(3):806-815. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4714-y. Epub 2016 Jul 23. Erratum in: Eur Spine J. 2018 Oct;27(10):2663. PMID: 27448810.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00586-016-4714-y

21.Okuda, S., Oda, T., Miyauchi, A., Haku, T., Yamamoto, T. and Iwasaki, M., 2006. Surgical outcomes of posterior lumbar interbody fusion in elderly patients. JBJS, 88(12), pp.2714-2720.

https://journals.lww.com/jbjsjournal/Fulltext/2006/12000/SURGICAL_OUTCOMES_OF_POSTERIOR_LUMBAR_INTERBODY.19.aspx

22.Rajaee, S.S., Bae, H.W., Kanim, L.E. and Delamarter, R.B., 2012. Spinal fusion in the United States: analysis of trends from 1998 to 2008. Spine, 37(1), pp.67-76.

https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/fulltext/2012/01010/spinal_fusion_in_the_united_states__analysis_of.12.aspx

23.Ruetten, S., Komp, M., Merk, H. and Godolias, G., 2008. Full-endoscopic interlaminar and transforaminal lumbar discectomy versus conventional microsurgical technique: a prospective, randomized, controlled study.

https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/Fulltext/2008/04200/The_Failed_Back_Surgery_Syndrome__Reasons,.00002.aspx

24.Weber H. Lumbar disc herniation. A controlled, prospective study with ten years of observation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983 Mar;8(2):131-40. PMID: 6857385.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6857385/

25.Berríos-Torres, S.I., Umscheid, C.A., Bratzler, D.W., Leas, B., Stone, E.C., Kelz, R.R., Reinke, C.E., Morgan, S., Solomkin, J.S., Mazuski, J.E. and Dellinger, E.P., 2017. Centers for disease control and prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017. JAMA surgery, 152(8), pp.784-791.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/article-abstract/2623725

26.Bisgaard, T., Klarskov, B., Rosenberg, J. and Kehlet, H., 2001. Characteristics and prediction of early pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Pain, 90(3), pp.261-269.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304395900004061

27.Gan, T.J., Habib, A.S., Miller, T.E., White, W. and Apfelbaum, J.L., 2014. Incidence, patient satisfaction, and perceptions of post-surgical pain: results from a US national survey. Current medical research and opinion, 30(1), pp.149-160.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1185/03007995.2013.860019

28.Kehlet, H. and Dahl, J.B., 2003. Anaesthesia, surgery, and challenges in postoperative recovery. The Lancet, 362(9399), pp.1921-1928.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673603149665

29.Ostelo, R.W., De Vet, H.C., Waddell, G., Kerckhoffs, M.R., Leffers, P. and Van Tulder, M., 2003. Rehabilitation following first-time lumbar disc surgery: a systematic review within the framework of the cochrane collaboration. Spine, 28(3), pp.209-218.

https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/Fulltext/2003/02010/Rehabilitation_Following_First_Time_Lumbar_Disc.3.aspx

30.Sigmundsson, F.G., Kang, X.P., Jönsson, B. and Strömqvist, B., 2012. Prognostic factors in lumbar spinal stenosis surgery: a prospective study of imaging-and patient-related factors in 109 patients who were operated on by decompression. Acta orthopaedica, 83(5), pp.536-542.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/17453674.2012.733915

31.Epstein, N.E., 2013. The risks of epidural and transforaminal steroid injections in the spine: commentary and a comprehensive review of the literature. Surgical neurology international, 4(Suppl 2), p.S74.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3642757/

32.Kreiner, D.S., Hwang, S.W., Easa, J.E., Resnick, D.K., Baisden, J.L., Bess, S., Cho, C.H., DePalma, M.J., Dougherty II, P., Fernand, R. and Ghiselli, G., 2014. An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. The Spine Journal, 14(1), pp.180-191.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1529943013014502

33.Leven, D., Passias, P.G., Errico, T.J., Lafage, V., Bianco, K., Lee, A., Lurie, J.D., Tosteson, T.D., Zhao, W., Spratt, K.F. and Morgan, T.S., 2015. Risk factors for reoperation in patients treated surgically for intervertebral disc herniation: a subanalysis of eight-year SPORT data. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume, 97(16), p.1316.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5480260/

34.Lebow, R.L., Adogwa, O., Parker, S.L., Sharma, A., Cheng, J. and McGirt, M.J., 2011. Asymptomatic same-site recurrent disc herniation after lumbar discectomy: results of a prospective longitudinal study with 2-year serial imaging. Spine, 36(25), pp.2147-2151.

https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/fulltext/2011/12010/Asymptomatic_Same_Site_Recurrent_Disc_Herniation.7.aspx

35.Ostelo + Oosterhuis, T., Ostelo, R.W., van Dongen, J.M., Peul, W.C., de Boer, M.R., Bosmans, J.E., Vleggeert-Lankamp, C.L., Arts, M.P. and van Tulder, M.W., 2017. Early rehabilitation after lumbar disc surgery is not effective or cost-effective compared to no referral: a randomised trial and economic evaluation. Journal of physiotherapy, 63(3), pp.144-153.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1836955317300681

36.Thakur JD, Sonig + Kingwell SP, Curt A, Dvorak MF. Factors affecting neurological outcome in traumatic conus medullaris and cauda equina injuries. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25(5):E7. doi: 10.3171/FOC.2008.25.11.E7. PMID: 18980481.

https://thejns.org/focus/view/journals/neurosurg-focus/25/5/article-pE7.xml

37.Weinstein, J.N., Tosteson, T.D., Lurie, J.D., Tosteson, A.N., Hanscom, B., Skinner, J.S., Abdu, W.A., Hilibrand, A.S., Boden, S.D. and Deyo, R.A., 2006. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. Jama, 296(20), pp.2441-2450.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/204281